Sugarbush’s iconic French bistrot – and the man behind it.

The screen door slams shut behind me as I walk briskly into the bar of Hogan’s Pub, the small, windowed restaurant atop Sugarbush Resort Golf Club with eastern views of the Green and White Mountains. I quickly glance around to see if I can locate my lunch date, admonishing myself for my tardiness, and hoping I haven’t kept him waiting too long. I slow down a notch, catch my breath, and cast my eyes about the bar.

It’s a sunny spring day, just past noon, and I don’t expect to see customers on the stools, but the bartender is chatting amiably with a well-coiffed gentleman wearing a gray golf shirt with a green sweater thrown casually around his shoulders. The man is perched on a stool, with an air of elegance, sipping a glass of red wine.

Ahhh. I have a moment of recognition as I recall that this is not a normal business lunch, but a lunch date with a Frenchman, and in France, people do sit at bars at noon, and wine at lunch is mandatory.

Henri Borel, the original proprietor of Chez Henri, the notable French bistrot in historic Sugarbush Village, is deep in conversation at the far end of the bar with the server and another patron or two. This is standard protocol for Henri, who has a knack for pulling people out of their solitary states, making them feel comfortable, and engaging them in dialogue about almost anything.

After we share greetings and settle ourselves at a table on the sun-splashed deck, our conversation turns to food. I join him in a glass of wine, and ask him what he is considering off the menu.

“I think I am going to have a soup and a hot dog, maybe,” Henri suggests. “A hot dog is something that reminds me of when I used to go to UVM to watch a game … when my son François was playing soccer.”

I am surprised that Henri is having a hot dog and soup—clam chowder, to be precise. I had expected something more gourmet from the man who first brought French cuisine to Sugarbush. But the more I get to know him, the more I understand that there is nothing at all pretentious about Henri Borel, and that he enjoys a hot dog equally as much as he enjoys beef Bourguignon … for its uniqueness, for its timelessness, and for the story it tells.

Henri’s lunch order leads us to a short discussion of his family: his wife of more than fifty years, Rosie, and their two children, Françoise and François. (Truth be told, it’s not until three-quarters of the way through our lunch that I realize Henri has two children with almost the same name. “That’s confusing!” I finally admit. Henri agrees: “Yes, for them, for us, for everyone”—including Georgetown University, he says, which assumed that “Françoise” was a boy’s name and placed her in an all-male dormitory after she was accepted as an undergraduate.)

I could happily spend all afternoon chatting amiably with Henri about nothing in particular, but I heed my list of questions, and ask Henri to take me on his journey from France to Sugarbush.

Henri Borel was born in 1926 in Avignon, a city in the southeast of France on the banks of the Rhône River. As a youth he recalls spending Thursday afternoons—his day off from school—with his grandfather, cleaning out oak barrels used for wine storage. His grandfather was one of the first wine merchants in Avignon, selling a red wine (Gigondas) and a rosé (Lirac), which he recalls as “simple drinking wines.” Today, both wines are sought-after French varietals.

Henri joined the French Armed Forces in 1944, just after D Day, and journeyed to Alsace-Lorraine for a six-month tour of duty that would pass through the Black Forest. Shortly thereafter, in 1945, peace was declared, and his army unit was sent to the war-ravaged, struggling city of Berlin. His unit was woefully unprepared for the scarcity of food in the city. He recalls one situation where the men had to approach a British unit for food. (The French troops were given donuts.) And another, where his unit hunted for food in a park in the middle of Berlin, shooting and then cooking “two beautiful deer.” Henri’s normally cheery disposition flattens, and his heavily accented voice reveals a wistfulness brought on by his recollections: a burned-out city, a starving population. “All accidents of life are part of life,” he muses.

Shortly after the war, Henri traveled to England, intent on improving his English skills. He found work with Group Captain Geoffrey Cheshire, one of the most highly decorated British fighters of World War II, who had opened a large home in Hampshire to house and care for those in need. After working there for the good part of a year, Henri heeded the advice of a beautiful woman he met there to “go out and see the world.” He accepted a job on a merchant marine ship, and began his journey.

Over the next several years, Henri’s merchant marine work took him to New Zealand, Panama, Seattle, and South America. On a short leave, Henri toured Paris, where, while walking along the Champs-Élysées, he spotted an Air France office with a sign soliciting recruits. Henri was soon offered a position as a steward with Air France, and continued his travels, this time by air.

As Henri lists the names of places he visited while working for Air France—Rio de Janeiro, St. Martin, Alaska, Japan, Tehran—he adds that he skied in both Japan and Tehran. “I called it skiing, though I did not know how to make a turn,” he says, chuckling.

I am curious to learn where Henri first learned to ski, knowing that these days, he skis an average of fifty times a year. Henri mentions Olivier Coquelin, a fellow Frenchman who plays a key role in Henri’s tale. Coquelin accompanied Henri on a trip to Saint-Gervais, in the French Alps, where they first sampled the sport of skiing.

Coquelin arrived at Sugarbush in the late 1950s to become the manager of Ski Club Ten—named after the “ten” original members. It had a roster of jet-setting clients, including club founders Hans and Peter Estin, brothers Oleg and Igor Cassini, Skitch Henderson, and the New York socialite Nan Kempner.

After several years running the club amid this high-octane crowd (who helped earn Sugarbush the nickname “Mascara Mountain”), Coquelin moved to New York City to open a nightclub—what would become the famed Le Club, in the East Fifties. Coquelin looked to Henri as his replacement. “Coquelin tells me, ‘Sugarbush is a beautiful place. It is sunny all the time.’ … I know he lies, but I came anyway.” Thus Henri, Rosie—newly pregnant with their son—and their six-month-old daughter, Françoise, moved into a single room on the first floor of Ski Club Ten. Henri thought he might stay for a year—but that was more than fifty years ago.

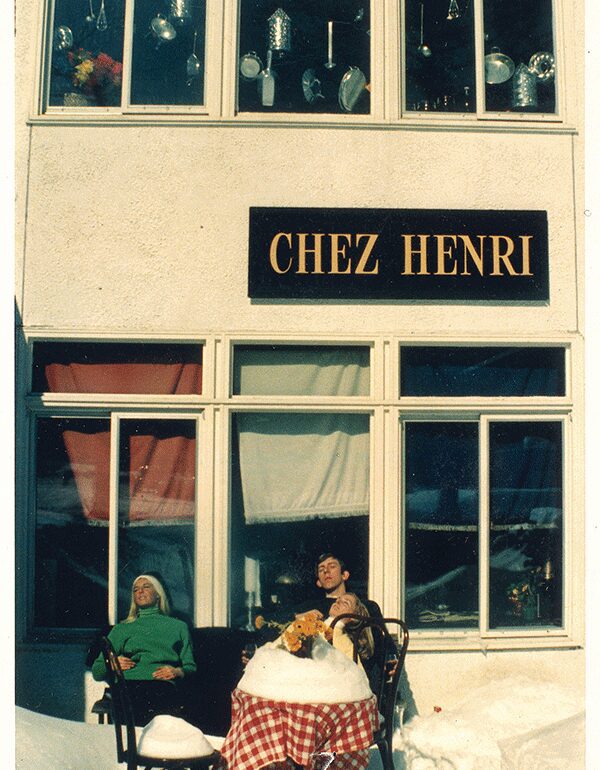

In 1964, Sugarbush founders Damon and Sara Gadd, close friends and colleagues of Henri’s, had an idea. Knowing Henri’s past experience running numerous restaurants (Ski Club Ten, the Sugarbush Inn, the Alpen Inn) and helping with Coquelin’s nightclubs in New York City and South Hampton, they asked Henri to open a restaurant at the mountain. The Gadds offered him free rent, insurance, and carte blanche access to a building just through the covered bridge in Sugarbush Village. Henri and Rosie decided to give it a try.

“We had no money,” Henri says, “and I don’t believe in new things.” He remembers the tribulations involved in infusing character into the new building. “There was no fireplace, so I stole the flue from the bathroom to make one. Then I spent a few days knocking down the walls to make arches.” Rosie decorated, supplying antiques from her shop, paintings on loan from or donated by artists, booths bought at auction, and Les Olivades fabrics imported from France.

The restaurant opened shortly before Christmas in 1964. There was no snow, the mountain was brown, it was raining, and Stein Eriksen, the Norwegian Olympian, had just arrived to run the Sugarbush Ski School. “I still remember Stein saying, ‘They told me there was snow at Sugarbush. Is this true?’ We had a problem at Sugarbush for Stein—no snow, and no Aquavit.” (Vermont’s stringent liquor laws were infamous even back then.) Snow did arrive shortly after Christmas, and things began to look up.

“Stein was my best customer,” Henri says. “He had a table by the fireplace.” He continues, “We were very lucky Stein was here. He was a very interesting man for everyone … well, maybe not for the husbands.”

Jean Claude Killy and Vincent Sardi were regulars, as was Igor Cassini—a close friend of Jackie Onassis’s, the brother of designer Oleg Cassini, and the writer of the syndicated column “Cholly Knickerbocker.” Henri’s customers over the ensuing years were a Who’s Who of American society, with Yoko Ono, the Kennedy clan, and the Heinz family among them.

“I was going to name the restaurant ‘L’Escargot,’” he says. But the Gadds, who spoke some French, had envisioned saying they were “dining at Henri’s place”—“chez Henri.” Prior to opening, while Henri was in South Hampton with Coquelin, he received the insurance certificate in the mail. It read “Chez Henri.” The Gadds had had the final say.

But L’Escargot is still a part of the story. In the late 1960s, Henri began a search for a business partner so he could spend more time with his family. At the recommendation of a friend, he drove to Montreal one evening to meet Bernard Perillat. Over an hour-long chat—and a plate of escargots—Henri and Bernard formed what would turn out to be a partnership that has lasted forty-five years.

Chez Henri has not changed much since 1964. The same artwork adorns the walls. The same fabric covers the tables. And the menu remains classically French: steak tartare, country paté, croque-monsieur, steak-frites, and, of course, escargots.

The staff, too, has a continuity. Jack Lonsdale, the Harvard graduate turned ski bum who ran the 1960s-era bus ferrying New Yorkers to Sugarbush, has tended bar for decades. “My notion of a business is that the most important thing is the crew,” Henri confides.

He thinks out loud about his own role in the restaurant. “My job is to always present the good side. Any situation is an interesting situation.” I am reminded that a crew needs a good captain. While Henri insists he is not the leader, it is he who makes the restaurant so enchanting. In December 2014, he will have run Chez Henri for fifty years. I ask him if he has big plans for the restaurant’s anniversary. “No plans,” he responds. “I am waiting for the big number. One hundred.” His loyal patrons may have other ideas.

Editor’s Note: In deference to Henri, we have spelled bistrot in the French manner throughout this article.