The design and creation of some of Sugarbush’s classic trails…

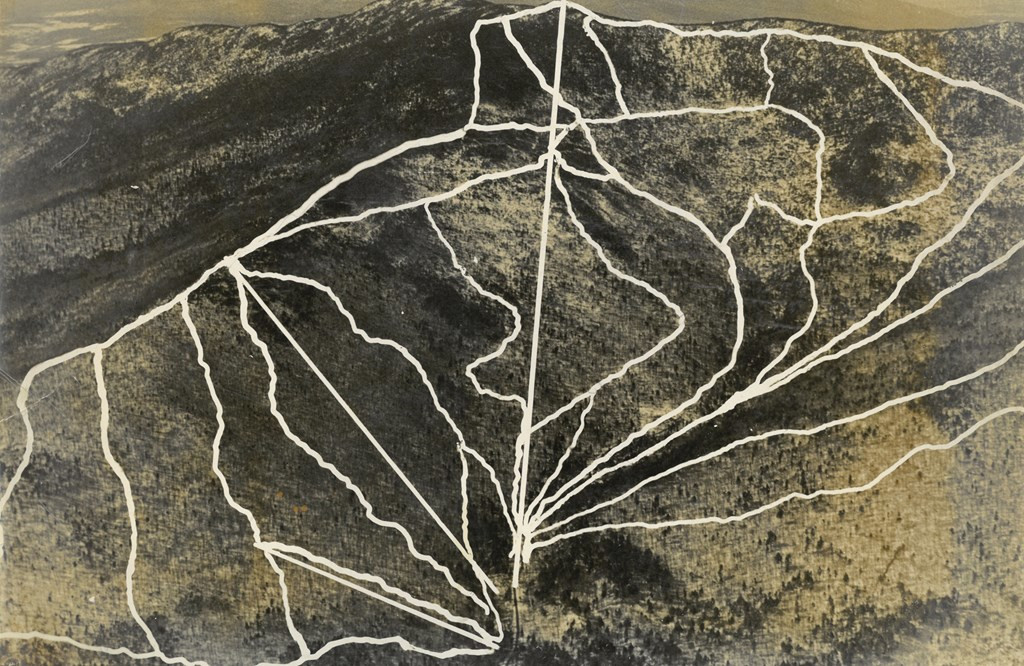

If you want to understand the original vision of Sugarbush’s trails, go to the Sugarbush Golf Club: before the golf course was there, this area was farm fields, and Jack Murphy, the first general manager of Sugarbush, settled on many of the trails from this spot, looking up at Lincoln Mountain. According to his son Mike, Jack “sat in the fields and drew a map of where he wanted the trails to go.” Based on his experience skiing in the larger mountains of the U.S. West, Jack looked to recreate a similar feeling on Lincoln Peak, with widely gladed runs, expansive views, and lots of challenging terrain. He also placed a premium on north-facing terrain for its snow-preserving quality.

Nearly all the trails were built when permitting was a much simpler process, before the passage of Vermont’s development law Act 250. Permission was required from the U.S. Forest Service for most of the Lincoln Peak trails, but Mt. Ellen was privately owned, so almost no permission was needed to start cutting. The original owner, Walt Elliott, designed the trails at Mt. Ellen (then known as Glen Ellen) largely using the same criteria that Jack Murphy used at Lincoln Peak—one of the reasons the two mountains have similar personalities. Bravo feels like Lift Line. Brambles and Semi-Tough are semi-Sleeperish. Elbow and Spring Fling are close relatives.

Trailbuilding techniques haven’t changed much over time, either. We’re still using handsaws, chainsaws, bulldozers, and, in some cases, dynamite (though no longer horses, which were used on some trails early on). The trees are either harvested, burned, buried, or pushed into the woods. The work was hard then, and it’s still hard now.

The first trail at Sugarbush, JESTER , followed the path of an old logging road. Beyond the end of the road, they pushed Jester to the summit of Lincoln Peak, which became the way up to install the original gondola and to cut the other trails. When it first opened, Jester was narrower and the turns were sharper than they are now.

Mike relates, “I remember skiing with my brother Chris off the gondola when I was seven or eight, doing nonstop top-to-bottom runs, with bumps everywhere because there was no grooming.” Mike’s sister, Kelly, also has fond memories of Jester: “I spent the most time on Jester; it was where we really learned to ski.”

RUMBLE was one of the original trails; at only ten feet wide to start, it was essentially one line. As Mike remembers, “It wasn’t really cut much, all hand work through the toughest, best terrain on the mountain. It always needed a lot of snow, but I have vivid memories of hiking over to Castlerock with John Egan in April 1978, after the lift closed for the season and we got a big late-season storm.” (Kelly, too, has a similar memory of skiing Rumble with Egan and her little brother Casey that same April.)

GLADE —renamed Murphy’s Glade after Jack Murphy died—was one of the runs where Jack wanted to mimic the western feel of open runs with trees. Once snowmaking and grooming entered the ski world, however, his feelings about trees on trails changed a bit. Running snowcats around the trees was difficult, and early snowmaking efforts tended to overload the trees, pulling them down. (Because snowmaking and trees aren’t a good mix, the only gladed trails with snowmaking are Murphy’s, Birch Run, and Sleeper; all of them are wide enough and have lost enough trees that snowblowing and grooming the blown snow can work.)

PARADISE was cut like Glade, with widely spaced trees, and remains a favorite for many expert skiers. Many of the most memorable Sugarbush images over the last sixty years have been shot on or near this trail, a true testament to Jack’s vision and work. Paradise also predates Mad River Glen’s trail of the same name, which has a similar feel.

SLEEPER ROAD was the first Gate House trail, allowing the lift and other trails in that area to be built—including Sleeper. Designed in the early 1960s as an easier gladed trail—significantly easier than Paradise—Sleeper is now one of the most popular trails for all ages.

The original BIRDLAND trail was close to where STEIN’S RUN is now, but was allowed to grow in, as it was exposed and constantly stripped of snow by wind. Stein Eriksen missed the old Birdland, which was the widest fall-line trail on the mountain, and convinced Jack to build Stein’s Run to replace it.

Glen Ellen opened in 1963, and FIS and Lower FIS were completed two years later, designed by Walt Elliott to meet FIS (International Ski Federation) standards for a downhill course. Lower FIS had a little extension below the traverse back to the base area, complete with its own rope tow, to meet the minimum vertical requirements. Many of the world’s best tested their mettle on the course, including local U.S. Ski Team member Marilyn Cochran.

Speaking of racing, INVERNESS was built as an original trail/lift area at Glen Ellen, and is now a designated U.S. Ski Team Development Site. Inverness is home to the Green Mountain Valley School’s training center, where future U.S. Ski Team members build their skills and strength under the tutelage of world-class coaches.

RIEMERGASSE (originally known as Bagpiper, but renamed for Win Smith’s original Sugarbush partner, Joe Riemer, who died in 2001) helped many people learn how to ski as part of Mt. Ellen’s learning area. The Sunshine Double (“Sunny D”) lift served the trails and was replaced last year with the Sunny Quad. These days, it’s the resort’s main freestyle terrain park—a prime training ground for some of today’s hottest skiers and snowboarders, including Sugarbush’s illustrious Diamond Dog freestyle team.